Practice in Context : TURNITINwholedoc

Ashley Bickerton

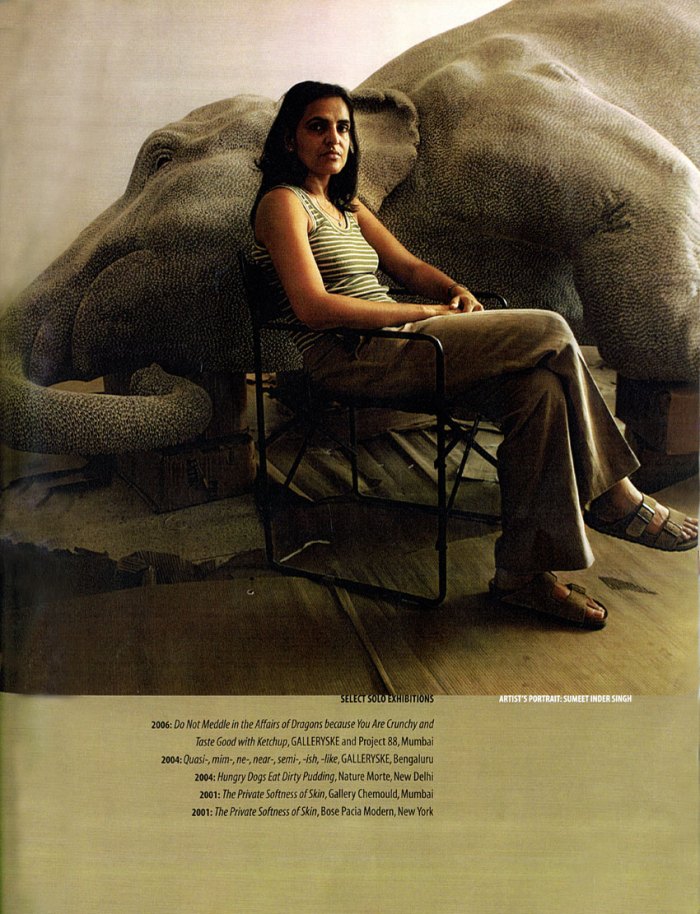

Bharti Kher

introduction :

I like to think that through my practice I can sort of somehow manage, this play, with material alchemy magic- that your transform materials that are not specifically linked to country place location geography place or history. Ive always thought that my practice has- or doesn’t really deal with the concerns of authenticity or culture as per say –

Because ive come from a space outside india, its not, i don’t feel like I have this idea of, that i can belong in a unique or authentic way which is why, allot of the timesI play with these ideas of misinterpretation of culture-the idea of the authentic.

… this idea of who you are — I think it is a question that plauges allot of artists because- your are not really able to cartmentalise the idea of a place or space — at the end of the day everyone has history and everyone have geography- biology science etc but it doesn’t create a sense of uniqueness in any individual.

The sense of the ‘hybrid’- hybrid women is that the self is multiple ”

Interview taken from : Interview online – Very influential towards practice and PIC-

CHRYSANNE:

Do you feel as if you have two countries in your head, England and India? Is there an interesting dialogue between them? When you moved to India, from Indian heritage but born in England, were you seen as an outsider?

BHARTI:

I was an outsider in both places. Poor me. Lucky me. Often I had conversations about the idea of authenticity because I think within the first few years when I arrived in India, it was very difficult—I mean to find a place, I wasn’t really Indian enough, and so how could I comment on the culture?

CHRYSANNE:

I remember that …

BHARTI:

“You’re not from here.” And I remember being afraid to say what I thought, but eventually, I just had to say: “I don’t believe in authenticity. I think it is bullshit.” I don’t think you have to be from a specific place to experience a more profound “anything.” If we are going to talk about authenticity of cultures, then it’s a completely fucked up prospect, especially in relation to experiencing art. Because art touches something that is common to us all. So nationalism is not my agenda. I couldn’t care less where I was from or where you are from. If your art is going to define you by your place, that is something that I am not actually interested in at all.

CHRYSANNE:

Neither am I.

BHARTI:

This is something that I have actually been forced to think about more than I thought I would, because people ask a lot about this idea of India, and what it means to be Indian artist. My first answer is always: “Well have you seen the demography of this country?” I mean it is so large. You may live in Europe. It takes me four hours to get from the north of India to the south of India. It takes you four hours from London to Moscow. To take on and represent this huge geography with 400 living languages and closing fast on two billion people…. How is it possible for art to talk about this in a way that means more than that sum total of statistics? I think it is absolutely impossible to think that art somehow clears a path of definitions of who you are; that there are codes you can read and then eureka! To answer questions when there isn’t one answer. The role of art for me is not to answer but to ask. Sometimes the eyes that see every day don’t see everything. So who is right? And more than that, why is my agenda to specifically examine my foreignness so that you get it? What if that doesn’t interest me?

CHRYSANNE:

Exactly.

SUSAN:

Outsiders can often see things that are invisible to everyone else because so many things are taken for granted by the insider.

BHARTI:

Yes. I think you are forced to do that because when you do not speak the language, other sensory perceptions have to take over and kick in, because you don’t hear so you don’t speak much. I didn’t speak Hindi. It took me about two and half years to learn how to speak the language, whether or not I felt comfortable talking to people in between was irrelevant.

SUSAN:

Do they still detect that you are from somewhere else?

BHARTI:

I am a foreigner still in many ways, pretend as I may. My kids tease me about my Hindi, especially my accent, as I used to do to my mother actually, about her English accent—she still has an Indian accent after all these years. You don’t lose these things; they are ingrained.

It’s interesting, you asked if there are two countries in my head. It’s really about memory, and I think your memory has such a profound effect on the way you experience things. “Do you have two heads?” Yes.

CHRYSANNE:

One of the reasons I asked, is that I often feel that I have many countries in my head. In the art world, with the stress on the Biennials, where artists represent their countries, what does it mean to represent a country? I think that artists want to be artists first. Maybe they do not identify with their country or even want to represent their country. There is a pressure to categorize artists: they are American artists, Canadian artists, Greek artists, Indian artists, English artists. It is a form of nationalism: the Indian show, the Italian show and so on. Artists are pushed into these categories, and maybe it isn’t really their choice, and they would want to break out of them.

BHARTI:

It’s all corrupted! We say: “Yes, okay I’ll be in the show, it’s fine.” At least your work gets seen. And then it’s an inconvenience because how do you break out after you have been categorized and filed away.

Bharit Kher, ‘Hybrid series: self portrait’, 2007, digital C-print, 45.54 x 54.65 cm. Image courtesy Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai.

Bharti Kher, ‘Hybrids series: family portrait’, 2004, digital C-print, 76.2 x 114.3 cm. Image courtesy the artist and Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai.

Yinka Shonibare

Shirin Neshat